CZECH CHAMBER LARP THROUGH THE YEARS (PART 2)

CZECH CHAMBER LARP THROUGH THE YEARS (PART 2)

This half of the article ends our story about the evolution of chamber larp in the Czech Republic (and Slovakia). I started writing this essay as a by-product of the recent larp book Check Larps because I thought it was high time for reflecting on the past before the details vacated my mind for good. In the first part, I covered the first six years and the way the genre transformed from its first timid steps to an era when we had a chamber larp festival on every corner.

THE GOLDEN YEARS (2011-2013)

I ended the last part of the article with the 2010 larp Rocker and I noted that its controversial nature was not as important as some conscious design choices made by the author, Lujza Kotryová. There are a few things to add to that. Firstly, at that time, publicly saying “this game works with realistic erotic physical contact” was scandalous to an unprecedented degree. It made the larp’s popularity skyrocket, and I believe that it still counts as the best known and most frequently run chamber larp, alongside Moon. Basically everybody also had an opinion on the game, whether they’d played it or not. This was the first time the Czech community talked about issues that are still being debated now, at a time when we have the first larps working with people having sex as part of the game (such as Dekameron): Should larps have erotic content? Won’t the realistic nature of eroticism destroy the illusion of “playing at something”? Will it make us distort pre-written dramatic relationships through steering?1 And most importantly, is it socially acceptable to say that we were just doing that “in character”?

In any case, the taboo on real alcohol and real physical intimacy that had been in place before was broken. In the following years, this trend was replicated in larps such as Salon Moravia, Samael, Byznys a baroko (Business and Baroque) and (even stronger) the adaptation of the Nordic larp Kink and Coffee, which was run at one of the last Larpvíkends.

Now the next thing, what we call conscious design. Around 2010-2011, the Czech larp community was already quite large, but it was still quite interconnected. Local communities were interlinked with personal relationships. The hard core of players and organizers was around a few hundred people strong and they all knew each other from different festivals around the country. They exchanged design know-how and that subconsciously set certain norms on design and quality.

This was naturally helped a lot by the abovementioned Odraz conference and its publications. It is telling, after all, that Pavel Gotthard’s article Píšu dobrý komorní larp a vím o tom (I’m writing a good chamber larp and I know it) is still the most quoted source in Czech diploma theses focused on larping. That’s no mean feat considering it was published after the conference in 2011! It is sad that there are still no newer relevant sources on larp design in Czech, but we also have to admit that the main concepts in the article (the unique feature, topic, and framework of a larp) are still valid even today. After all, the author mentions the need for testing a larp before it is run and that only became common practice in recent years.

The environment where almost everyone knew everyone did not last long. Within a few years, the community grew rapidly, and we might say that Court of Moravia’s old dream of making larp mainstream finally came true. Some new players saw it as an experience for one night or one weekend and had no desire to continue playing or start making their own larps. Other newbies, however, stayed and became the main pillars of the following developments. Naturally, other players would later find they had enough of the format and pick other larp types.

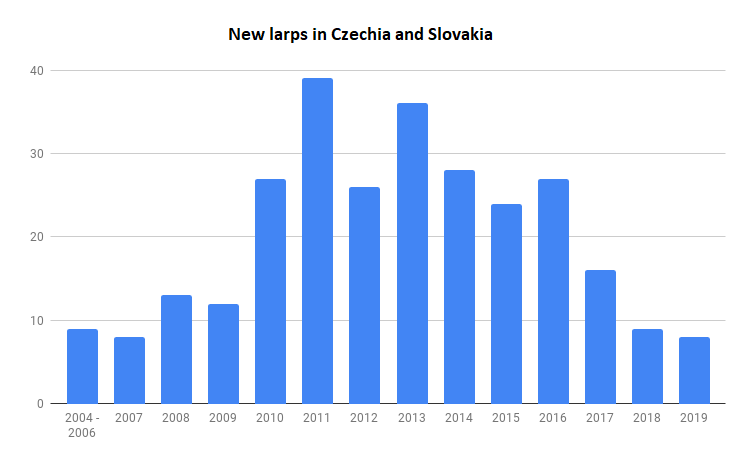

When looking at the games themselves, the striking feature is especially the jump in the number of new larps. My (incomplete) records that I have been keeping for a few years show that a record number of 39 new pieces was written in 2011. That is triple the number of chamber larps that the Czech scene larps had produced only three years back. With this number, it is a bit hard to look for clear trends, but let’s try.

BLEED, EXPERIMENT, AND LEGEND

I have already mentioned the popularity of the so-called ”Czechoslovak jeep”. After 2012, the number of larps in this genre went through the roof. At the same time, the form became more worn and shallower. “Czechoslovak jeep” larps were often relationship or family dramas, and rather than creative takes on the format, the games were often reduced to a railroad with scripted scenes. The original freedom and experimental nature innate to jeepform could therefore only be found in translated larps from abroad that we started running (Drunk, Fat Man Down). Still, I believe that we have been through this jeep madness: both because of the handful of truly excellent games that this gave rise to, and because this scenic structure was carried on to other larps that would shed its theatrical nature (Cien Años de Soledad), or emphasize it in a creative way (Telenovela, Bucañero).

Why are we talking about the “golden years”, though? Well, it’s not just about the sheer number of new larps and the adaptation of design principles. Most importantly, something changed the games themselves and the way they worked. We got the first truly good larp comedies, like Telenovela, Škola (School), or FK Perseus, where the players took the roles of a football team. I actually still believe that comedy is one of the most difficult genres to convey through the medium of larp and Kamil Buchtík, the author of two of the three larps mentioned above, deserves a Golden Globe (of larp) for his contributions.

We also did a lot of translating and adapting. If we count translated chamber larps, the number of new larps in these years would be even more striking.

There were a lot of them, but I’ll mention at least Doubt. The first runs in Brno were done by Michal Havelka and Vanda Staňková in 2012, and a lot of players left it with a profound feeling of “what the hell”. Things that were especially hard for Czech players to wrap their heads around at the time included stuff like: “OMG, somebody forgot to write half the larp!” or “Do you seriously expect us to drag our own romantic screwups to light here?” And then at the end: “Did we really spend eight hours here?” I’d say that while the term “bleed” had only been known by a few larp theorists a few years before, now with Doubt, it gained very clear dimensions.2

We also picked up a very peculiar habit: we started experimenting… Although of course if we look back at the early years, we could technically say that everything was an experiment, because no paths had been trodden before. Jakub Balhar wrote The Strings, a larp in which the players got tangled in a complex web of laws and clauses, while also getting tangled in a very real web of strings that tied the participants to special harnesses. Zuzana Hrnčířová designed a chamber larp that happened in the darkness. Her Terapie tmou (Darkness Therapy) was also remarkable because she got funded by a grant that allowed her to make the first ever tour of the Czech Republic with her larp. I also cannot leave out the crazy computer game adaptation Kytky versus Zombie (Plants vs. Zombies). Lesser-known games worth mentioning also include the crazy crossover Don Juan aneb Strašlivé hodování (Don Juan or a terrible feast), which combines a telenovela aesthetic with dancing, plucking feathers, and absurd theatre.

Last but not least, there are three striking larps that must be mentioned. What they have in common is that, like the owls in Twin Peaks, they are not what they seem. I cannot avoid major spoilers, but since the larps are all quite old and in Czech, I don’t think it really matters. All these games have a sort of a second plane, a major revelation that completely changes their meaning in the end.

At first glance, I speak only da truth looks like the twin of the dirty cop drama Odznak (The Badge), mentioned in the previous part of the article. The interesting thing is that the players are divided into gang members and police officers in the beginning and the groups spend most of the game in separate rooms. The real revelation only comes in the final credits (yes, there are real credits), when the participants find out that the whole story is a biblical allegory, in which a dead mobster plays the role of Christ.

Moon, a western space opera and the larp with the most reruns in the Czech Republic, is a similar case. While Only da truth was inspired by The Wire, Moon draws on the super popular TV show Firefly. But again, it’s not primarily about the stories of space cowboys – the story is a clever parallel to the dilemma that Czechoslovakia faced in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement before World War II – do we surrender our home or face an insurmountably more powerful enemy against terrible odds?

Eliška Applová and Rado Hübl approached this method slightly differently. While for a short time, their Samael took up the mantle of scandal after Rocker, the message was completely different. The larp contained realistic physical intimacy, real alcohol, and even some (relatively) realistic violence, but at the end, the wild party feel is drowned out by an epilogue containing the statistics on sexual assault in the Czech Republic, which is also the secret underlying the main storyline of the whole piece.

All three of these games count amongst legends of the chamber larp scene of old. Other legendary pieces include Iure, Hranice (Border), L-World, Never let me go and many of the games that I have already mentioned. This clearly shows that in these years, authors were often drawing on experience from designing older games. That helped them know what motives to accentuate and how to design their pieces to create the right experience.

THE HARBINGERS OF A NEW AGE

The period of 2011-2013 also gave rise to a very significant sort of momentum that would impact the future of chamber larp in the Czech Republic profoundly: The onset of high-production content larps (even though we didn’t call them that yet). Let’s look at how it happened…

Some of the chamber larps of this time were already signalling a slow shift towards better production value. Moon, El día de Santiago, and Bucañero for example could no longer make do with your standard classroom and the costumes that players can supply. The Pirate larp Perla Karibiku (Pearl of the Caribbean) even had a VIP version, which added good food and drink on top of its splendid production. Still, these were quite isolated cases.

Things had already been set in motion a bit before that, with the creation of Projekt Systém (2009) by Court of Moravia. Suddenly we had a serious larp about a totalitarian regime, with robust plot design and game mechanics, and pre-written characters, which took place over three days in the realistic venue of a recreation camp from the Communist times. Costumes, full production, all-day catering, and mental terror all included.

In 2010, Central Bohemian designers came with Ardávské údolí (The Ardávia Valley), and a year later they ran their larp Porta Rossa, set in a renaissance town during a plague epidemic, which had almost film-like production values. From that point onwards, the machinery of big, high-production games was unstoppable. However,… when I say big, I don’t necessarily mean the number of players. Many high production larps of this type were actually quite hard to categorize. Skoro Rassvet, Salon Moravia, or Dance Macabre, for example, had between 3 and 8 hours of game time and (except for Dance Macabre) they did not have that many players, so we could technically easily classify them as chamber larps. But the experience as a whole also included workshops and in some cases an afterparty, so taking part in them usually took up an entire weekend.

This new trend also went hand in hand with more frequent and louder talk about the importance of pre-game preparation and the post-game phase (a debrief, reflection, and taking care of player safety in general). The aforementioned concept of “bleed” was in the foreground of this debate, though the meaning had shifted a bit.3 We started having discussions over whether the then common approach of “I want to feel emotionally shattered after the larp” was healthy. All this suddenly permeated the sphere of chamber larp as well, even though up to that point the common thing was to drown emotions in a pint of beer at the festival afterparty and limit reflection to questions like “what was your strongest experience in the game?”

It also seems undeniable that high-production content larps owe much to chamber larp. Their authors generally started in the chamber larp environment and tried out the fundamentals of design on making chamber larps. In the last period that we will mention, large-scale games with pre-written characters started pushing out the demand of chamber larps more and more. It is worth mentioning that most current content larp authors over 30 started writing and playing chamber larps around the period of 2011-2013 at the latest.

In the beginning of this article, I mentioned how interconnected the community was around 2011. I should also say that as the chamber larp scene rapidly grew, the situation became less clear. New towns started their own festivals: Plzeň, Pardubice, Lipník, or Ostrava. These attracted new young authors who took their first designer steps in their own little communities. The side effect of the increase in new debuts was, as could be expected, that a number of them were only run a few times.

Knowledge sharing and theoretical reflection slowed down a bit once again. The reasons are simple: the pioneers of larp theory who stood at the start of the chamber larp boom were slowly leaving the scene, which paralyzed projects that had served for these exchanges up to that point. This buried the work on the Czech larp wiki, Larpedia, this portal, Larpy.cz, experienced a long hiatus, and the last Odraz conference took place in 2012.

But not everything was sad and in decline. 2012 also saw the start of Larp Database, and the first Czech larp podcast, Role, was launched only a little later. We also got new chamber larp initiatives, such as Hraj larp (Prague) and Hraju larpy (Brno). They took up the mantle of Court of Moravia and started organizing a chamber larp run every week or two. That reminds me: we also got our first chamber larp “assembly lines”. The first was Larpworkshop in Česká Třebová, while Brno even got a larp design course, Škool, that stayed active for several years. It was also a time when the first chamber larp authors passed their scenario on to a new organizing team. The honour belonged to the most famous chamber larp of the time: Moon.

THE SWAN SONG (2014-PRESENT)

I have to admit the last period could probably be divided into multiple parts. If we look at the chart of new original larps in Czechia, we can see that the boom of the previous era lasted for several years, before the numbers plummeted. Yet the new trend of players slowly shifting their interest to large content larps is clear. The truth is I succumbed to it as well, so I only played around fifteen chamber larps from this period myself.

When I mentioned the shift, I didn’t mean just the players; organizers were part of this trend as well. The most famous figures of the past five years started this era by producing new weekend-long content larps, rather than chamber larps. These included Legion: Siberian Story or De la Bête. Figuring out why this happened doesn’t seem hard: The high-production, 360° illusion of an authentic, wide-ranging world was no doubt more attractive than larping in Mrs. Currywinkle’s basement. The fact that the target group got older definitely also played a role. Spending a weekend away once every three months started feeling easier than scuttling around Prague every week for two hours of larping.

The further development of chamber larp therefore fell mostly in the hands of newcomers and the Larpworkshop patrons. As most traditional festivals fell into decline, the main marketplace for chamber larps shifted to events organized by the Hraj/u larpy weekly initiatives in big cities. An interesting opportunity for targeting players who’d never larped before was the annual Gamecon, which gradually broadened its larp selection.

While the chamber larp community grew smaller and more fragmented, we still got local communities now and then, centred around dedicated larpwrights who kept pushing the train onwards: EH Games in the Slovak Košice, StopTime in South Bohemia, or the not-so-new Crex in Ostrava.

Chamber larps also entered completely new environments where they could address completely new target groups, for example libraries or art galleries: such as Vendula Borůvková’s “art larps” Nový Eden (New Eden) and Člověkohodina (Man-hour). They also turned out to be useful in education: the historical project Post Bellum ran workshops in schools, Josef Kundrát created edu-larps to teach practical applications of science. Reflective experiential learning also found its intersection with chamber larp, in the form of projects like V kůži pacienta psychiatrické léčebny (In the Shoes of a Psychiatric Hospital Patient) and Cesta za snem (Pursuing a Dream).

It is also no surprise that in recent years, the larp medium got into contact with the theatre world. We could see that in the larp adaptation of Pomezí (Borderlands), originally a successful immersive theatre performance, which took place at the original theatre set, as well as in recent performances by Janek Lesák’s company The Game and Městečko Palermo usíná (Mafia).

I remember that, once it had become clear that the heyday of chamber larp was past, I predicted that the format could become a sort of experimental laboratory that would serve for testing new, bold concepts. That turned out to be an overly idealistic and mistaken idea, which did not suit the interests of both participants and authors. After all, unconventional, non-traditional larps had quite a lot of trouble finding players (such as Cien Años de Soledad).

Nevertheless, we did get interesting new takes, mainly because seasoned organizers wanted to make something original. That gave rise to the non-verbal Čí sny sníš (Whose Dreams Are You Dreaming), the abstract and improvisation-based Figurky (Pawns), or the civil larp Nejdelší zpoždění (The Longest Delay) where four out of six players take the roles of the protagonists’ thoughts. Orlov, in return, represented an interesting fusion of larp and computer game, with a spaceship crew dealing with their internal struggles and external threats, while also flying their ship using a computer simulation.

My favourite chamber larp from this period is the narrativist Karavana (Caravan), an intentionally non-dramatic game inspired by Arabian Nights. A group of people sitting around the fire in a tent in the desert tell stories based on the organizers’ input.

We also kept translating lots of larps from other countries, and this period also gave rise to a number of comedies, often with quite bizarre topics. These allowed you to try out the roles of Greek gods, sardines, or preschoolers: Medvídek Pú (Winnie-the-Pooh), Poprask na Olympu (A Scandal at Mt. Olympus), Prom, Pískoviště (Sandbox), Ryby (Fish), Výjimeční vyšetřovatelé 2 (Incredible Investigators 2). Chamber larps also started breaking out of the conventional mould more frequently: Some were not played in one room (such as the outdoor Stezky šamanů (Paths of the Shamans), or lacked pre-written characters and plots – Figurky, Hrací skříňka (Music Box), Poprask na Olympu, etc.

THIS IS NO THEATRE, MY BOY…

Almost every chapter of this article mentions an article by Pavel Gotthard, so this one won’t be an exception. In 2013, he published a provocative debut novel “Léky smutných”, a lovingly teasing commentary on larp escapism. A year later, he wrote his essay “Není pravda” (Not true), a call for authenticity and understated acting. He sees potential for that both on the side of the player, who can use these to make their performance deeper and more believable, and on the side of the author, who can be challenged to look for deeper motivations for character conflicts. If we learn to observe everyday details and behaviour patterns, we’ll improve our ability to generalize our own experience to give a broader account of interpersonal relationships.

I believe the author’s view was informed by larps oriented on an everyday setting, such as Samael or Doubt. In a previous chapter, “It’s alive”, I mentioned that in the previous periods, a “good, dramatic scene” was closely linked to a slightly overdramatic, exaggerated acting style. Pavel’s article suggests the direction in which the scene had moved since then. This was not only due to the players, but the larps themselves. Building shallow plots around “you want something from Frank, and you hate Henry because he stole your girl” was suddenly not enough anymore. This desire for nuance and authenticity was later also reflected in larger dramatic larps, such as spolu/sami (together/alone) and Příliš krátká neděle (Sunday Ends Too Soon). In chamber larp, it became the signature look for larps by Lucie Chlumská and Zuzana Hrnčířová.

Zuzana became a pioneer of new approaches, which often toed the line between larp and experiential psychological games. Her larps intentionally blur the boundaries between player and character by making the participant answer difficult questions, such as: “Are you happy with where your life is going?” The one-person larp Probuzení (Awakening) can answer that. “How do you communicate in your relationships?” Explore that in My dva (The Two of Us). If there is somebody we can point to as a larpwright who developed their unique auteur style over the years, it’s definitely Zuzana.

Lucie Chlumská’s name, on the other hand, gradually became a mark of quality. The success of her L-World was followed by the social drama Takové hodné děti (Such Good Kids) and most importantly her hit piece Příběhy hříchu (Stories of Sin), set in an Irish Magdalene Laundry. Příběhy hříchu had two remarkable elements: Firstly, its scene design was unique and resembled a film mise-en-scène. The space where the player was standing determined whether they were in the dominant part of the scene or in the background. Secondly, the larp also confirmed a trend of the previous few years and showed how the demographics of the audience had changed. The game had solely female roles, to be played by women – although there were also several all-male crossgender runs. If we look back at the older games, for example those by Court of Moravia, mentioned in the previous part, we can see that in most cases, only a third of the roles at best were for women. 4

Now it seems the time has come to conclude my piece. I have to admit I don’t know exactly how to do that without sinking into nostalgic rambling. The thing I was thinking about the most as I was writing was how much we had progressed in both larp design and how we play larps in those fifteen years. We no longer have to teach Paul not to act as Paul in the game, but as the character he is playing. (Almost) nobody is shocked that larping is not just a specialized hobby for a handful of nerds, but an activity that’s accessible to anyone. We are not surprised that there are think-pieces on larp national weeklies and that larps get their own documentaries. We don’t clutch our pearls at sometimes getting served real whiskey in the in-game saloon, rather than apple juice. We know how to show in-game emotions by means other than screaming our lungs off. We understand what words like design and metatechnique mean. And I could go on forever…

The truth is that chamber larp has become an endangered species and there’s no point crying about that; it’s just the times that are changing. But before it started singing its swan song, it had given us a lot. When I look back, I also see another thing that we should perhaps take away from its history: Its boldness. The courage to go where no one has gone before. To try entirely new paths, even at the risk that you will hit a dead end.

- The term “steering” refers to players influencing the in-game reality for off-game reasons, according to Jaakko Stenros. An example might be preferring an in-game romantic partner who is off-game attractive to us to others.

- You can find out more about how the larp developed and how it was received in Czechia in Michal Havelka’s article http://larp.cz/?q=cs/clanek/5952/doubt-aneb-pribeh-jednoho-larpu

- Czech larpers still use “bleed” or “bleeding” to denote a player feeling sad or blue during or after the larp. In larp theory, the term „bleed” is more nuanced and refers to the transfer of (any) emotions between the character and the player.

- It was, and to some extent still is, customary that characters were either male or female and people picked them based on their gender. Over time, as the proportion of women in the community grew, this meant a strong push for writing more and more interesting female characters. Crossgender play (people playing character regardless of their gender), as well as characters outside of the binary have only become somewhat common in recent years.